Honor Killings In Iran (first Half Of 1404)

Researcher: Rezvan Moghaddam

Introduction

This study examines and analyzes documented cases of honor killings in Iran during the first six months of the year 1404 in the Solar Hijri calendar (Farvardin–Shahrivar 1404 / March–September 2025). The research is based on data that have been systematically, continuously, and through field-based monitoring collected and documented by Rezvan Moghaddam.

The findings of this sustained effort have so far been published in the form of several independent investigative reports and are widely used as reliable sources by human rights activists, researchers, international organizations, and campaigns opposing violence against women. In addition to statistical documentation, these reports analyze patterns of violence, the relationship between victim and perpetrator, geographical distribution, victims’ ages, and the social and legal contexts in which these crimes occur.

The objective of this research goes beyond recording numbers and events. It aims to expose the structural dimensions of honor killings, critically challenge cultural narratives that justify violence, and emphasize the responsibility of the state in prevention, protection of potential victims, and reform of discriminatory laws. This research is an effort to transform marginalized and silenced suffering into data, voice, and a clear demand for justice and the right to life.

Historical Background of Honor Killings

Honor killing is a complex phenomenon rooted deeply in the history of patriarchal societies. In traditional social systems, women were perceived as instruments for reproduction and the preservation of tribal power. What was controlled was not merely individual behavior, but women’s reproductive capacity and the survival of the clan.

Throughout history, honor-based violence has functioned as a mechanism for enforcing hierarchy and preserving tribal social order. Sustained through unwritten customary norms and, in some cases, formal legal frameworks, these traditions prioritize collective honor over individual rights, thereby reproducing cycles of violence across generations.

Contemporary Definition of Honor Killings

Honor killings are among the most extreme forms of gender-based violence rooted in control over women’s bodies and sexuality. They arise from patriarchal structures and socio-cultural systems that define a woman’s body not as her individual right, but as family property.

In these killings, a woman is murdered by a male family member or someone close to her, such as a boyfriend due to her behavior, clothing, personal choices, or even rumors and unfounded suspicions. Honor killings emerge from a dangerous combination of male ownership over women’s bodies, domestic violence, and the support or tolerance of legal and governmental structures.

These crimes are not necessarily based on objective facts; suspicion alone is often sufficient to justify violence. Honor killings are rarely impulsive acts. Rather, they are organized attempts to preserve patriarchal norms, positioning women’s right to life against the preservation of family reputation. In many societies, such crimes remain unpunished or receive lenient sentences because they are framed as “private family matters.”

In patriarchal systems, a man’s honor is directly tied to his perceived ability to control the behavior and sexuality of women related to him wives, daughters, or sisters. Consequently, women who refuse forced marriage, request divorce, choose employment without male consent, engage in relationships outside marriage, or are even victims of sexual assault may be deemed a source of “shame” and targeted for violence. These killings are often premeditated and implicitly or explicitly supported by other family members.

Overview of the Present Study

Data Collection and Study Population

The study population consists of 118 documented cases of honor killings recorded on the website of the Stop Honor Killings Campaign during the first half of Solar Hijri year 1404 (March–September 2025).

Data were collected through systematic media monitoring and direct reporting. Journalists and the campaign’s monitoring team track relevant cases daily through domestic media outlets and field sources. After identity verification and confirmation of honor-related motives, each case is registered on the campaign’s website and then entered into a structured database (Excel) for analysis.

This mixed-method approach—combining public sources and exclusive campaign data—ensures the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the dataset. Data visualization software (such as Excel or Python) was used to generate charts and identify temporal and spatial patterns.

Data Analysis Methods

The analysis consists of two main components:

Quantitative Analysis

Focuses on all 118 cases to answer questions such as: What is the most frequent relationship between perpetrator and victim?

Qualitative Analysis

Select cases are examined narratively, considering motives, community reactions, and histories of domestic violence. This approach provides contextual depth and helps identify underlying patterns not visible through quantitative data alone. The final findings integrate both approaches.

It is crucial to note that many honor killings remain unreported or deliberately misclassified as suicide, accident, or family dispute. Therefore, these 118 cases represent only the tip of a much larger iceberg overshadowing the lives of millions of women in Iran.

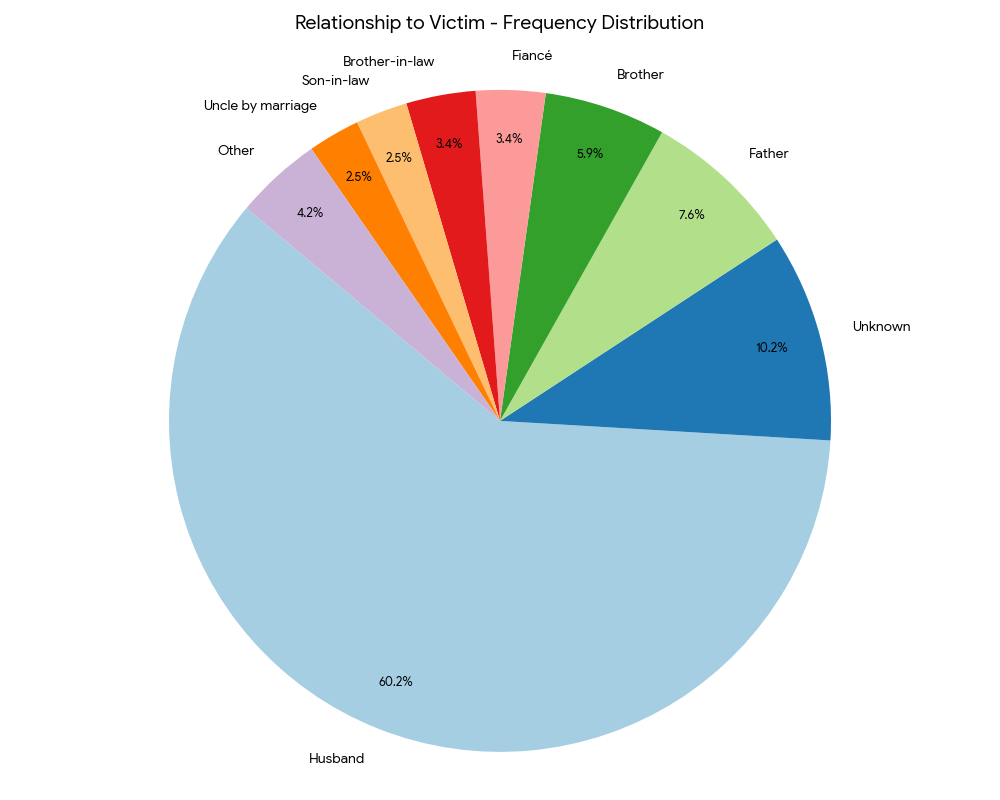

Table 1. Frequency Distribution of Perpetrator–Victim Relationship (N = 118)

| Relationship to Victim | Count | Relative Frequency (%) |

| Husband | 71 | 60.17 |

| Unknown | 12 | 10.17 |

| Father | 9 | 7.63 |

| Brother | 7 | 5.93 |

| Fiancé | 4 | 3.39 |

| Brother-in-law | 4 | 3.39 |

| Son-in-law | 3 | 2.54 |

| Uncle by marriage | 3 | 2.54 |

| Other | 5 | 4.24 |

| Total | 118 | ~100 |

This chart clearly illustrates the distribution of the “Relationship to Victim,” highlighting that Husband is the most frequent category at 60.2%.

Summary of the Pie Chart:

- Husband: 60.2% (71 cases)

- Unknown: 10.2% (12 cases)

- Father: 7.6% (9 cases)

- Brother: 5.9% (7 cases)

- Others: The remaining categories (Fiancé, Brother-in-law, Son-in-law, Uncle by marriage, and Other) collectively account for approximately 16.1% of the total cases.

Analysis: Husbands account for over 60% of cases, highlighting lethal violence within marital relationships. The dominance of close family members underscores the intra-familial nature of honor killings.

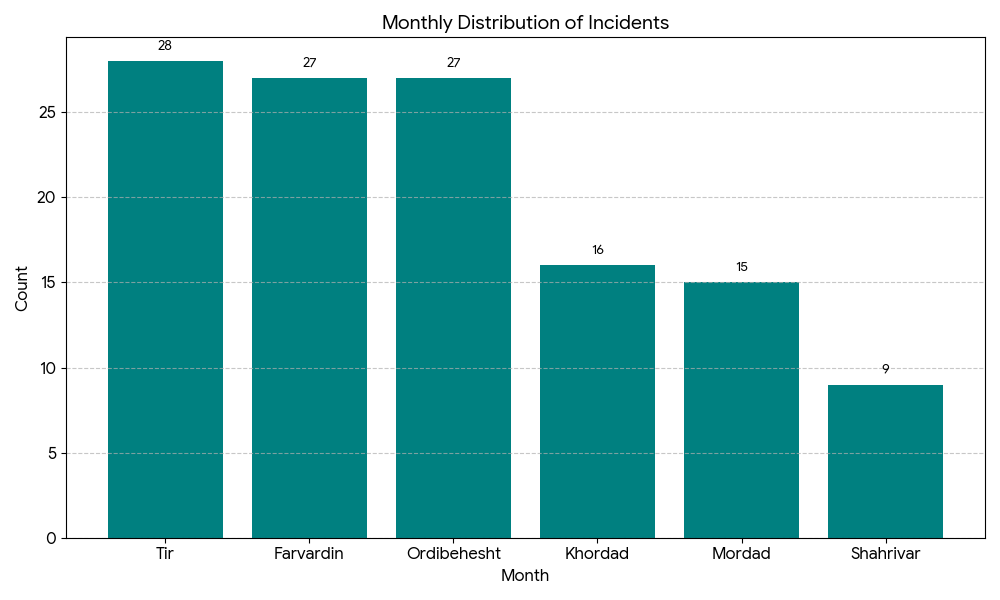

Table 2. Monthly Distribution of Killings (Solar Hijri 1404 / March 20th –September20th 2025)

| Month (English / Persian) | Count | Percentage |

| Tir (July) | 28 | 23.73 |

| Farvardin ( -March 20th-April) | 27 | 22.88 |

| Ordibehesht (May) | 27 | 22.88 |

| Khordad (June) | 16 | 13.56 |

| Mordad (Agust) | 15 | 12.71 |

| Shahrivar (Sep20 th) | 9 | 7.63 |

| Total | 118 | 100 |

Interpretation: Over 70% of killings occurred between Farvardin and Tir (March–July 2025), suggesting predictable seasonal risk patterns, possibly linked to increased family interaction during Nowruz and early summer.

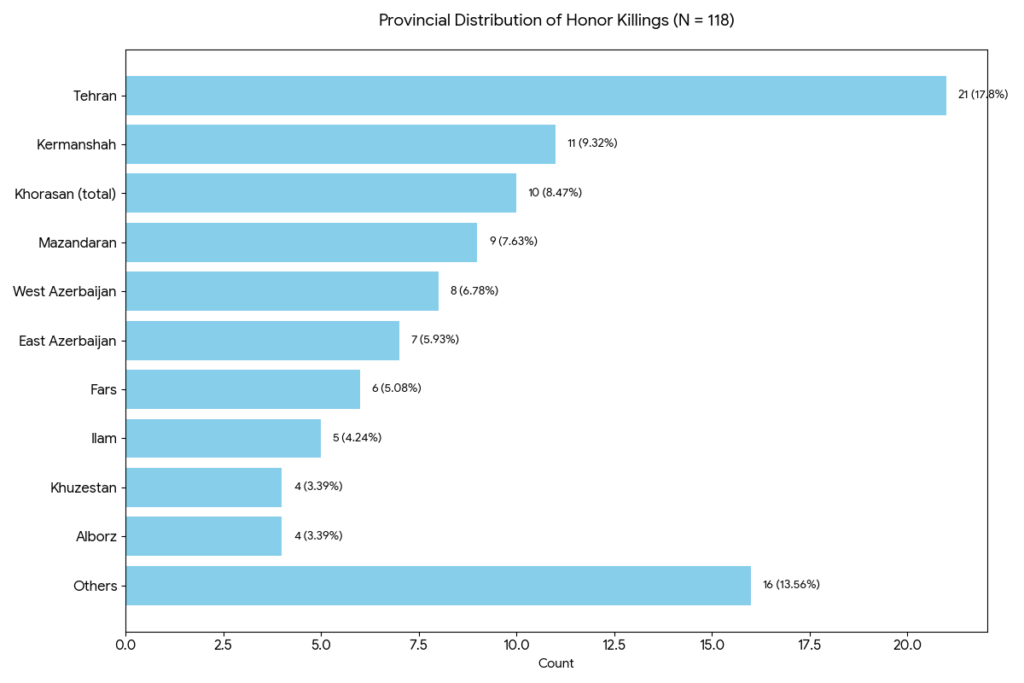

Table 3. Provincial Distribution Summary (N = 118)

| Province | Count | Percentage |

| Tehran | 21 | 17.80% |

| Kermanshah | 11 | 9.32% |

| Khorasan (total) | 10 | 8.47% |

| Mazandaran | 9 | 7.63% |

| West Azerbaijan | 8 | 6.78% |

| East Azerbaijan | 7 | 5.93% |

| Fars | 6 | 5.08% |

| Ilam | 5 | 4.24% |

| Khuzestan | 4 | 3.39% |

| Alborz | 4 | 3.39% |

| Others | 16 | 13.56% |

| Total | 118 | 100% |

Analysis of the Geographical Distribution of Honor Killings

Table 3 regarding geographical distribution indicates that the occurrence of these crimes across the country is not uniform; rather, it is highly concentrated and asymmetrical.

- Primary Hotspots: Tehran Province, with 21 recorded cases (17.80% of the total), is identified as the highest hotspot for honor killings during this period. This figure is nearly double the frequency of the second most frequent province. Kermanshah Province with 11 cases (9.32%) and the Khorasan region with 10 cases (8.47%) follow in the subsequent ranks. Collectively, these three primary hotspots account for more than one-third (approximately 35.6%) of all killings. However, it should be noted that the high statistics in Tehran are likely influenced by factors such as the province’s high population ratio and methodological issues (such as more active media coverage and news monitoring in metropolises compared to smaller towns where secrecy is more prevalent).

- Regional Concentration: The data shows a significant concentration in the western, northern, and northwestern provinces. Specifically, Mazandaran with 9 cases (7.63%), West Azerbaijan with 8 cases (6.78%), and East Azerbaijan with 7 cases (5.93%) alongside Kermanshah constitute a major portion of the statistics. This geographical pattern highlights the need for further studies regarding the specific cultural and social factors of these regions.

- Scattered Distribution and the Tail End: More than half of the provinces listed in the table have an absolute frequency of 4 cases or fewer. Provinces such as Khuzestan, Alborz, Lorestan, Kurdistan, and Hormozgan, each with 4 cases (3.39%), have statistics at a low-to-medium level compared to the primary hotspots. At the end of the distribution, provinces like Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari recorded only 2 cases (1.69%), while the remaining 6 cases (5.08%) are distributed among 6 other provinces. This indicates a phenomenon with a national scope but high local concentration.

Summary: While Tehran Province stands out as the highest statistical point, this is influenced by population size and media coverage. Concentrations in western and northern provinces indicate regional structural risks. The collective concentration in border and northern provinces suggests that the phenomenon of honor killings during this period has regional roots of varying intensities. Despite the concentration at the top of the table, the frequency distribution spans more than 20 provinces, demonstrating that the femicide phenomenon is not limited to a specific region but is a national and structural crisis.

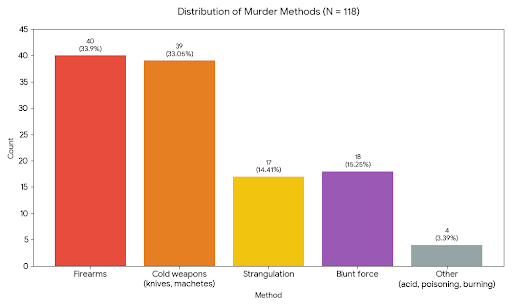

Table 4. Distribution of Murder Methods (N = 118)

| Method | Count | Percentage |

| Firearms | 40 | 33.90% |

| Cold weapons (knives, machetes) | 39 | 33.05% |

| Blunt force | 18 | 15.25% |

| Strangulation | 17 | 14.41% |

| Other (acid, poisoning, burning) | 4 | 3.39% |

| Total | 118 | 100% |

Interpretation:

Interpretation:. The analysis of Table 4, which presents the frequency distribution of methods used in honor killings across 118 documented cases, indicates that the overwhelming majority of these crimes were carried out using violent means with a high lethal potential. Firearms, with 40 cases (33.90%), and bladed weapons (including knives and machetes), with 39 cases (33.05%), appear almost equally and together account for more than two-thirds (approximately 67%) of all killings, emerging as the dominant methods in the commission of these crimes. This pattern reflects both the high accessibility of such weapons and a pronounced inclination among perpetrators to employ fast and highly effective means of killing. The next category includes methods such as beating with blunt objects (18 cases, 15.25%) and strangulation (17 cases, 14.41%), which together comprise approximately 30% of the remaining cases and are more likely to occur in indoor settings and close-contact confrontations. In contrast, “other methods,” such as acid attacks, poisoning, or burning, represent the lowest frequency, with only 4 cases (3.39%).

Harsh and unconventional methods (“other tools”): The use of acid, aluminum phosphide (“rice tablets”), vehicular assault, or burning—although relatively low in frequency is significant in terms of the extreme level of violence and the deliberate intent to inflict additional pain, suffering, or humiliation on the victim, indicating a high degree of hostility and resentment. Moreover, the relatively high prevalence of methods such as strangulation (17 cases) and beating with blunt objects (18 cases) underscores the individualized and domestic nature of these killings, in which the perpetrator was a person in very close proximity to the victim (most often a husband or close relative) and relied on readily available instruments within the household environment.

Over two-thirds of killings involved firearms or knives, indicating high lethality and premeditation.

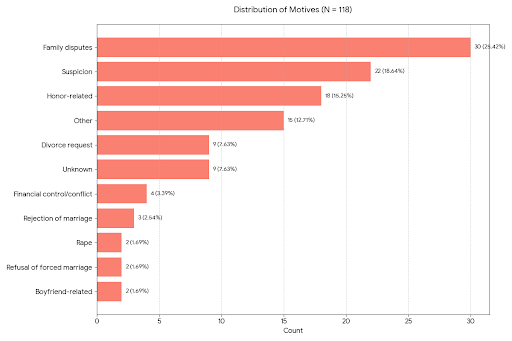

Table 5. Distribution of Motives (N = 118)

The analysis shows that Family disputes, Suspicion, and Honor-related motives are the most common factors, accounting for approximately 59% of the total cases.

| Motive | Count | Percentage | |

| Family disputes | 30 | 25.42 | |

| Suspicion | 22 | 18.64 | |

| Honor-related | 18 | 15.25 | |

| Divorce request | 9 | 7.63 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 7.63 | |

| Rejection of marriage | 3 | 2.54 | |

| Rape | 2 | 1.69 | |

| Refusal of forced marriage | 2 | 1.69 | |

| Boyfriend-related | 2 | 1.69 | |

| Financial control/conflict | 4 | 3.39 | |

| Other | 15 | 12.71 | |

| Total | 118 | 100 | |

| |

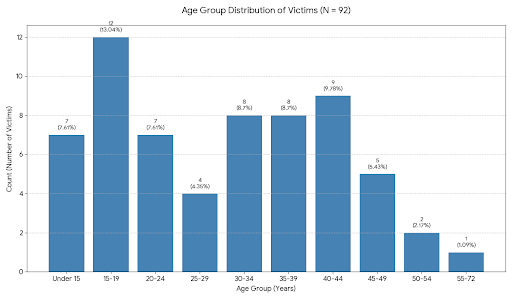

Table 6. Frequency Distribution by Age Group (N = 118)

| No. | Age Group (Years) | Absolute Frequency (Count) | Relative Frequency (%) |

| 1 | Under 15 (Children) | 7 | 7.61% |

| 2 | 15–19 (Adolescents) | 12 | 13.04% |

| 3 | 20–24 | 7 | 7.61% |

| 4 | 25–29 | 4 | 4.35% |

| 5 | 30–34 | 8 | 8.70% |

| 6 | 35–39 | 8 | 8.70% |

| 7 | 40–44 | 9 | 9.78% |

| 8 | 45–49 | 5 | 5.43% |

| 9 | 50–54 | 2 | 2.17% |

| 10 | 55–72 | 1 | 1.09% |

| Total | Subtotal (Known Age) | 92 | 68.50% |

| — | Unknown Age | 26 | 31.50% |

Age Analysis

The age of perpetrators was known in 41 cases, with a mean age of 39 years. Victims’ ages were recorded in 92 cases, with a mean age of 32 years. This age gap supports a hierarchical power dynamic, where older men exercise authority over younger women. A significant concentration of victims’ falls within adolescence (15–19), highlighting extreme social control over young women.

Analysis of Age Group Distribution

Based on the frequency table (N = 118, with 92 known ages), the following trends are evident:

- Most At-Risk Group: The 15–19 age group (adolescents) has the highest frequency with 12 cases (13.04%). This suggests that young women in their late teens are disproportionately targeted.

- Vulnerability of Minors: A significant number of victims (7 cases, 7.61%) are under the age of 15, highlighting the extreme vulnerability of children in these contexts.

- Young Adulthood: When combined, victims between the ages of 15 and 44 make up the vast majority of the known data, indicating that women in their prime reproductive and productive years are most frequently the victims of these crimes.

- Decline in Older Groups: There is a notable decline in frequency as age increases beyond 45, with very few cases recorded in the 50–72 age range.

- Data Limitation: A significant portion of the total sample (31.5%) consists of “Unknown Age” cases. This high percentage of missing data is a common challenge in analyzing such reports and may slightly skew the relative frequencies of the known groups.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the killing of women in Iran is rooted in multi-layered structural factors, including socio-economic conditions (such as poverty and financial stress), geographical concentration (higher prevalence in specific regions), and legal–institutional deficiencies (the absence of effective protective laws for women). The deliberate concealment of identifying information and details about perpetrators except in cases where crime scene reconstruction is unavoidable significantly obstructs rigorous criminological analysis, particularly the examination of victim perpetrator relationships and recurring patterns of violence.

In many cases of so-called “honor”, perpetrators benefit from lenient punishments or the non-disclosure of their identities, which constitutes a form of soft protection by social (male-centered/manlistic) and judicial structures. This systematic opacity perpetuates the cycle of violence and implicitly communicates to society that the killing of women by male relatives is a more socially tolerable or “less criminal” act.

The statistical analysis of temporal, spatial, instrumental, and demographic distributions across 118 documented cases of femicide indicates that this phenomenon in Iran is neither random nor merely individual, but rather structural and predictable. These patterns reflect the persistent failure of protective institutions and the endurance of patriarchal social structures.

The findings demonstrate that honor killings in Iran are structural, predictable, and systemic, rooted in patriarchal norms, legal impunity, and socio-economic stressors. Lenient punishment, concealment of perpetrators’ identities, and institutional silence perpetuate violence and normalize the killing of women by close male relatives.

Predictive Temporal–Spatial Indicators

Concealment of perpetrator information:

The high proportion of missing data regarding the age and identity of perpetrators (with age identified in only 41 cases) represents a structural failure that undermines judicial transparency. This lack of data prevents precise criminological analysis and obstructs the design of evidence-based preventive interventions.

Lethal instruments:

More than 67% of the killings were committed using firearms or bladed weapons (knives and similar instruments). The dominance of such lethal means indicates that a substantial proportion of these crimes were carried out with clear intent to kill and, in many cases, prior planning, rather than as spontaneous outcomes of accidental disputes.

Spatial concentration:

Tehran Province, with 17 recorded cases, shows the highest frequency, followed by border and peripheral provinces such as Kermanshah and West Azerbaijan. This bipolar distribution suggests two distinct risk patterns:

- Metropolitan risk, associated with social disorganization and population density; and

- Structural–cultural risk, linked to poverty and the dominance of patriarchal traditions in marginalized and border regions.

The Discursive Misrepresentation of Femicide as “Family Disputes”

An important finding of this research concerns the systematic framing of femicide in state-affiliated media as the result of “family disputes” (ekhtelefāt-e khānevādegi) or “family killings.” This terminology is neither neutral nor accidental, but rather serves multiple political and ideological functions:

- Depoliticization of gender-based violence:

By labeling femicide as a private “family dispute,” structural gender inequality and state responsibility are obscured, transforming a public crime into a personal matter. - Evasion of legal accountability:

The term allows judicial institutions to avoid recognizing these killings as gender-based crimes, thereby justifying lenient sentences and the absence of legal reform. - Normalization of male violence:

Such language implicitly frames male violence as an understandable reaction to domestic conflict, rather than as a criminal act rooted in patriarchal power relations. - Erasure of gendered motive:

The concepts of “family killing” or “dispute” deliberately remove the gendered nature of the crime, concealing the fact that the overwhelming majority of victims are women and girls, killed by men in positions of familial authority.

From an analytical and ethical standpoint, the term “family killing” is conceptually invalid. Families do not kill; individuals operating within patriarchal power structures do. Similarly, “family dispute” is a misleading euphemism that masks femicide and contributes to its social normalization.

Policy Recommendations

To enable effective intervention, the following measures are recommended:

- Time- and place-based interventions:

Development of temporal spatial risk maps and the immediate strengthening of protective mechanisms (including shelters and emergency hotlines) in high-incidence provinces, particularly during spring and early summer. - Control of lethal means:

Implementation of stricter regulations on access to firearms and bladed weapons in high-risk regions and households with documented histories of violence. - Data transparency:

Legal obligation for judicial authorities to publish complete, disaggregated statistical data including perpetrator age and relationship to the victim to facilitate scientific research and enable public oversight of justice implementation.

Recommendations

- Temporal and spatial risk mapping with enhanced support services during high-risk months (Farvardin–Tir / March–July).

- Stricter regulation of access to firearms and cold weapons in high-risk regions.

- Mandatory transparency by judicial authorities through publication of disaggregated data to enable accountability and evidence-based prevention.

About writer and researcher:

Dr. Rezvan Moghaddam is a sociologist and women’s rights activist with a PhD in Gender Studies. She has been actively engaged in the Iranian women’s movement for over four decades, combining academic research with grassroots advocacy. As the founder of the Stop Honor Killings Campaign, she has systematically documented cases of femicide and honor killings in Iran, producing multiple investigative and analytical reports based on verified data and long-term field monitoring. Her research focuses on gender-based violence, patriarchal legal structures, and state accountability, and her work is widely used by human rights organizations, researchers, and international bodies.